Addressing

Code that controls a running game must be able to reach every object and component in order to move, scale, animate, delete and manipulate what the player sees and hears. Defold’s addressing mechanism makes this possible.

Identifiers

Defold uses addresses (or URLs, but let’s ignore that for now) to refer to game objects and components. These addresses consist of identifiers. The following are all examples of how Defold uses addresses. Through this manual we are going to examine in detail how they work:

local id = factory.create("#enemy_factory")

label.set_text("my_gameobject#my_label", "Hello World!")

local pos = go.get_position("my_gameobject")

go.set_position(pos, "/level/stuff/other_gameobject")

msg.post("#", "hello_there")

local id = go.get_id(".")

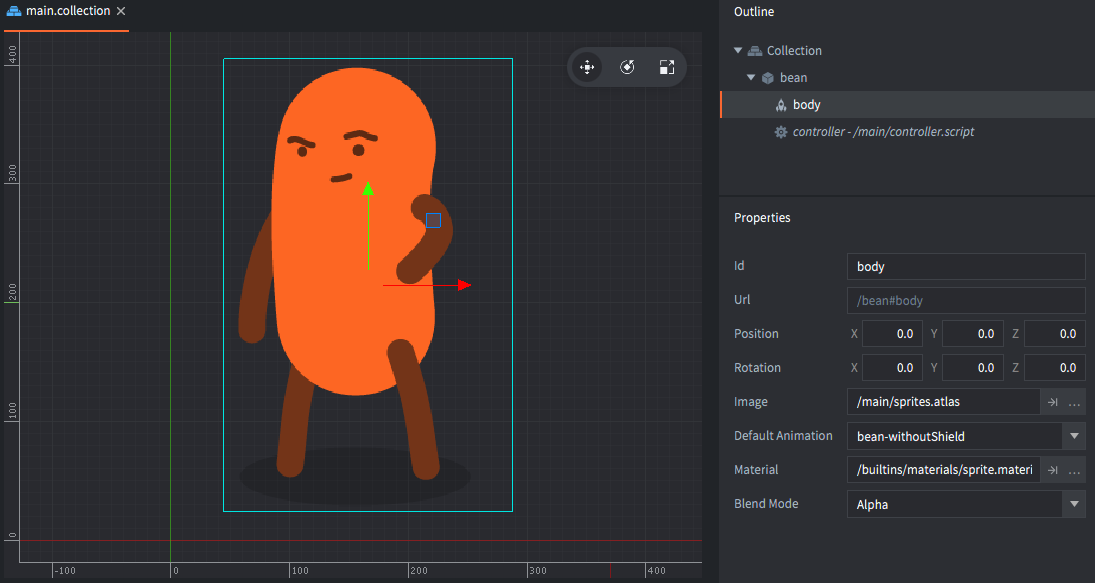

Let’s start with a very simple example. Suppose that you have a game object with a single sprite component. You also have a script component to control the game object. The setup in the editor would look something like this:

Now you want to disable the sprite when the game starts, so you can make it appear later. That is easily done by putting the following code in “controller.script”:

function init(self)

msg.post("#body", "disable") -- <1>

end

- Don’t worry if you’re puzzled by the ‘#’ character. We’ll get to that soon.

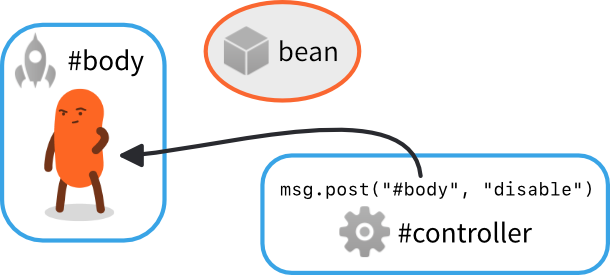

This will work as expected. When the game starts, the script component addresses the sprite component by its identifier “body” and uses that address to send it a message with the “disable”. The effect of this special engine message is that the sprite component hides the sprite graphics. Schematically, the setup looks like this:

The identifiers in the setup are arbitrary. Here we have chosen to give the game object the identifier “bean”, its sprite component has been named “body”, and the script component that controls the character has been named “controller”.

If you don’t choose a name, the editor will. Whenever you create a new game object or component in the editor, a unique Id property is automatically set.

- Game objects automatically get an id called “go” with an enumerator (“go2”, “go3” etc).

- Components get an id corresponding to the component type (“sprite”, “sprite2” etc).

You can stick to these automatically assigned names if you want to, but we encourage you to change the identifiers into good, descriptive names.

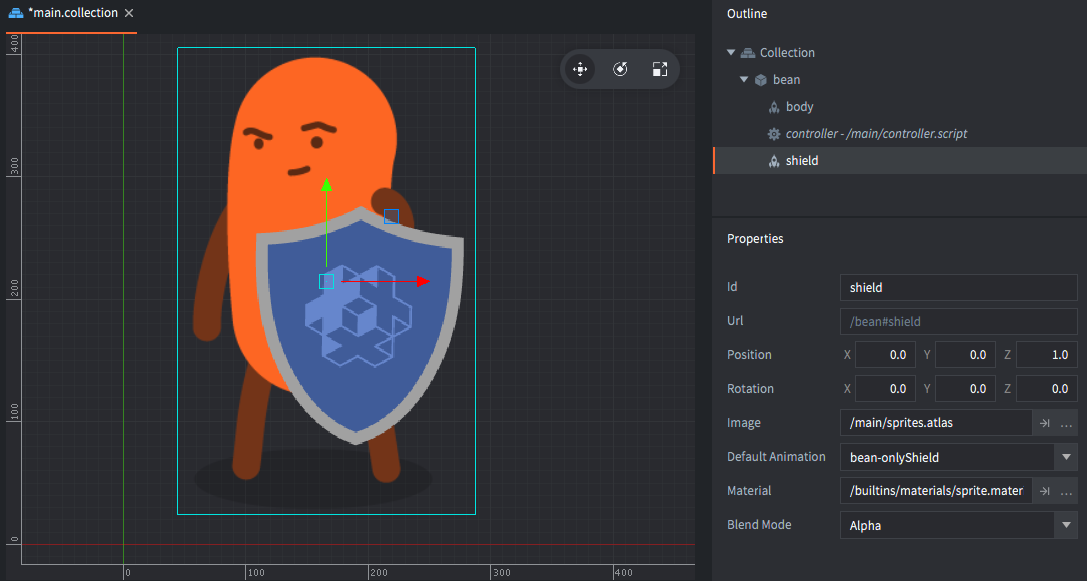

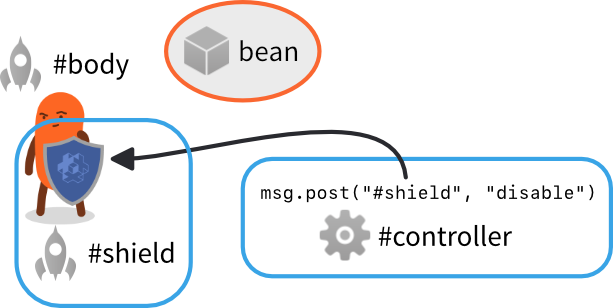

Now, let’s add another sprite component and give the bean a shield:

The new component must be uniquely identified within the game object. If you would give it the name “body” the script code would be ambiguous as to which sprite it should send the “disable” message. Therefore we pick the unique (and descriptive) identifier “shield”. Now we can enable and disable the “body” and “shield” sprites at will.

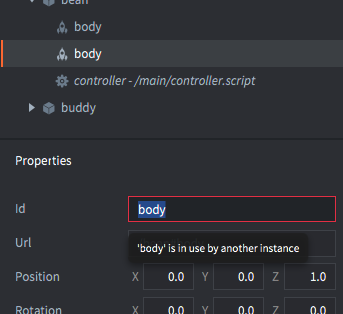

If you do try to use an identifier more than once, the editor will signal an error so this is never a problem in practice:

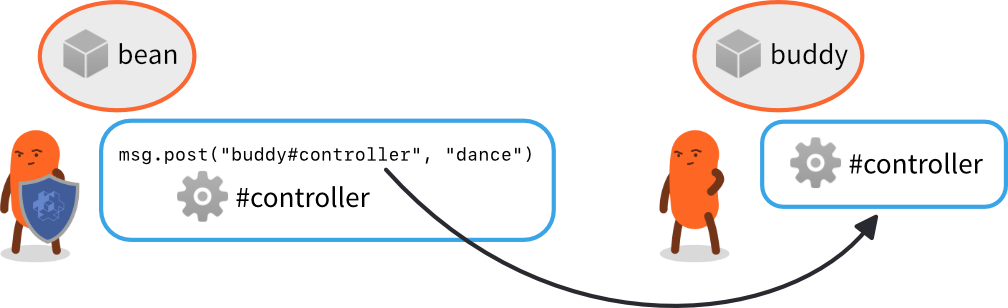

Now, let’s look at what happens if you add more game objects. Suppose you want to pair two “beans” into a small team. You decide to call one of the bean game objects “bean” and the other one “buddy”. Furthermore, when “bean” has been idle for a while, it should tell “buddy” to start dancing. That is done by sending a custom message called “dance” from the “controller” script component in “bean” to the “controller” script in “buddy”:

There are two separate components named “controller”, one in each game object but this is perfectly legal since each game object creates a new naming context.

Since the addressee of the message is outside the game object sending the message (“bean”), the code needs to specify which “controller” should receive the message. It needs to specify both the target game object id as well as the component id. The full address to the component becomes "buddy#controller" and this address consists of two separate parts.

- First come the identity of the target game object (“buddy”),

- then follows the game object/component separator character (“#”),

- and finally you write the identity of the target component (“controller”).

Going back to the previous example with a single game object we see that by leaving out the game object identifier part of the target address, the code can address components in the current game object.

For example, "#body" denotes the address to the component “body” in the current game object. This is very useful because this code will work in any game object, as long as there is a “body” component present.

Collections

Collections makes it possible to create groups, or hierarchies, of game objects and reuse them in a controlled way. You use collection files as templates (or “prototypes” or “prefabs”) in the editor when you populate your game with content.

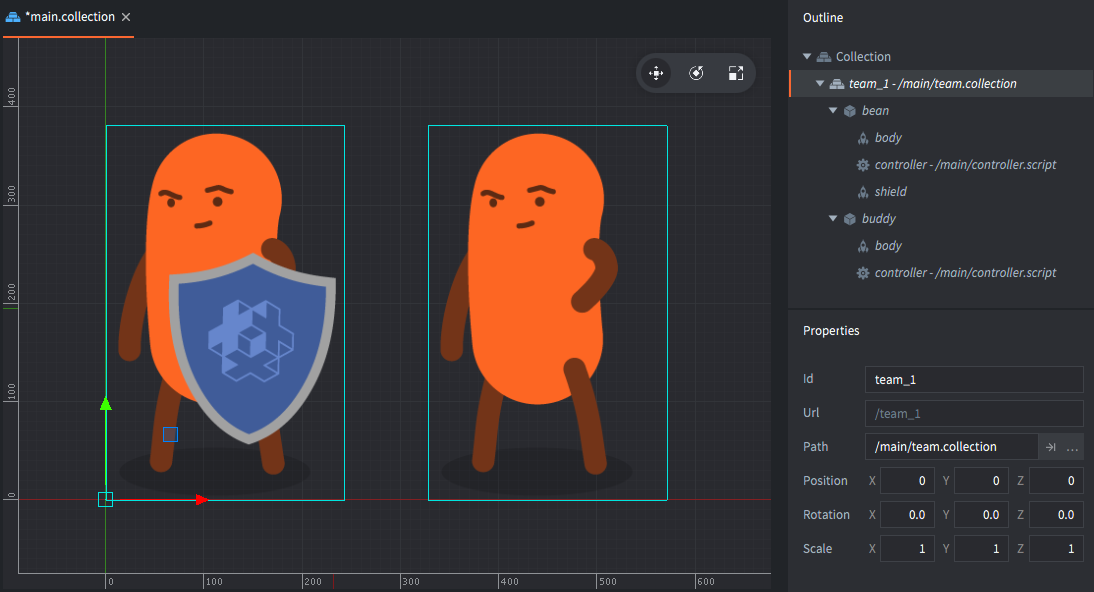

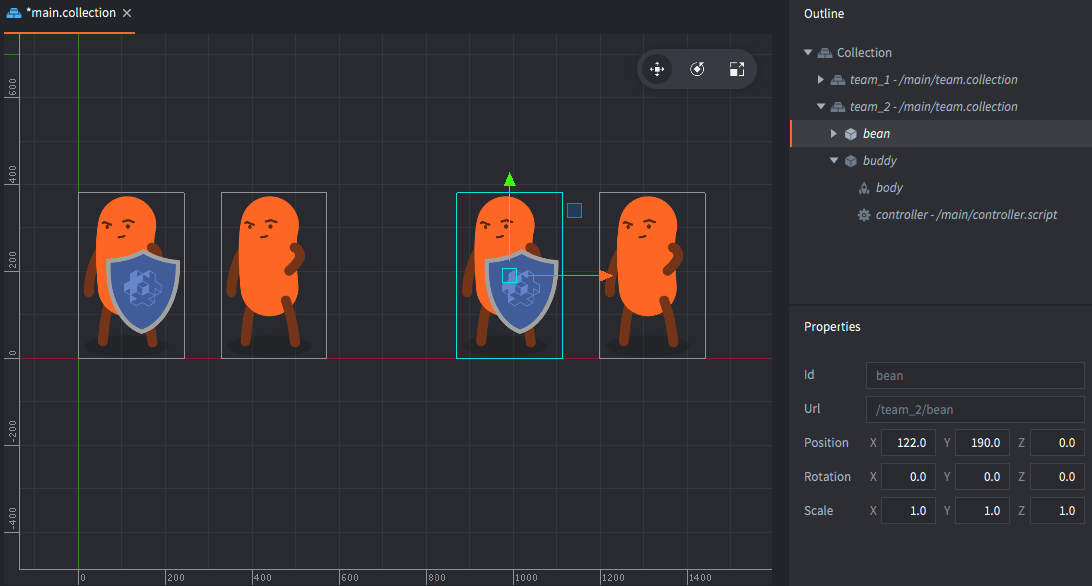

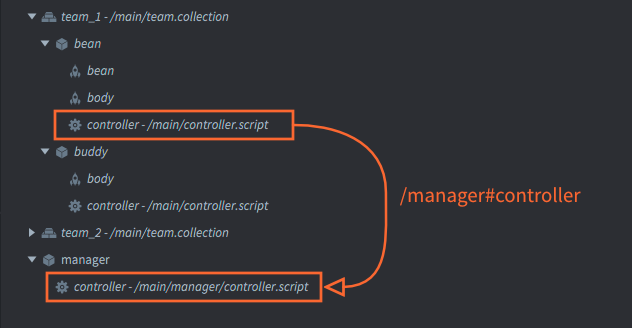

Suppose that you want to create a great number of bean/buddy teams. A good way to do that is to create a template in a new collection file (name it “team.collection”). Build the team game objects in the collection file and save it. Then put an instance of that collection file’s contents in your main bootstrap collection and give the instance an identifier (name it “team_1”):

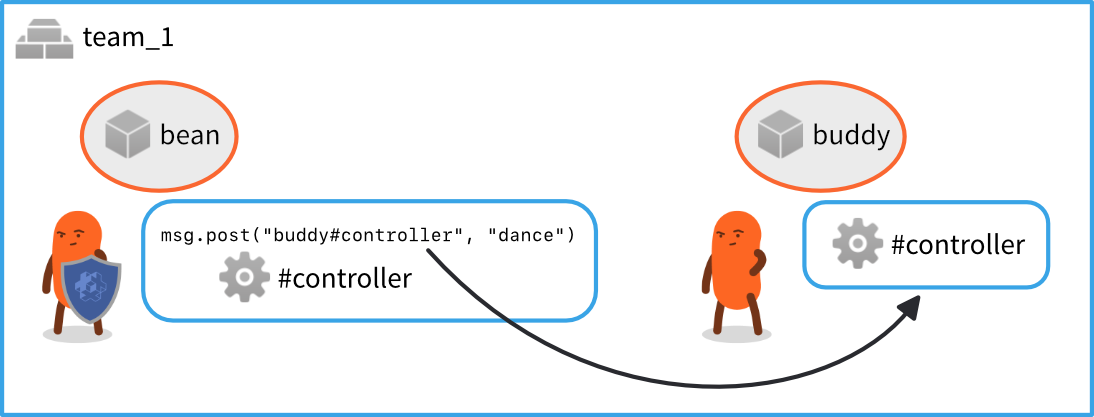

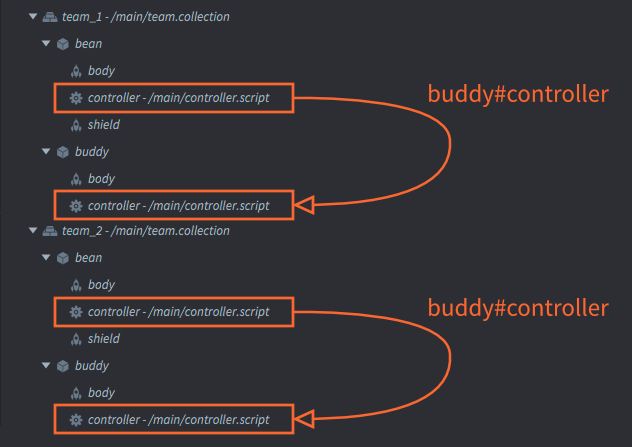

With this structure, the “bean” game object can still refer to the “controller” component in “buddy” by the address "buddy#controller".

And if you add a second instance of “team.collection” (name it “team_2”), the code running inside the “team_2” script components will work just as well. The “bean” game object instance from collection “team_2” can still address the “controller” component in “buddy” by the address "buddy#controller".

Relative addressing

The address "buddy#controller" works for the game objects in both collections because it is a relative address. Each of the collections “team_1” and “team_2” creates a new naming context, or “namespace” if you will. Defold avoids naming collisions by taking the naming context a collection creates into consideration for addressing:

- Within the naming context “team_1”, the game objects “bean” and “buddy” are uniquely identified.

- Similarly, within the naming context “team_2”, the game objects “bean” and “buddy” are also uniquely identified.

Relative addressing works by automatically prepending the current naming context when resolving a target address. This is again immensely useful and powerful because you can create groups of game objects with code and reuse those efficiently throughout the game.

Shorthands

Defold provides two handy shorthands that you can use to send message without specifying a complete URL:

.- Shorthand resolving to the current game object.

#- Shorthand resolving to the current component.

For example:

-- Let this game object acquire input focus

msg.post(".", "acquire_input_focus")

-- Post "reset" to the current script

msg.post("#", "reset")

Game object paths

To correctly understand the naming mechanism, let’s look at what happens when you build and run the project:

- The editor reads the bootstrap collection (“main.collection”) and all its content (game objects and other collections).

- For each static game object, the compiler creates an identifier. These are built as “paths” starting at the bootstrap root, down the collection hierarchy to the object. A ‘/’ character is added at each level.

For our example above, the game will run with the following 4 game objects:

- /team_1/bean

- /team_1/buddy

- /team_2/bean

- /team_2/buddy

Identities are stored as hashed values. The runtime also stores the hash state for each collection identity which is used to continue hashing relative string to an absolute id.

In runtime, the collection grouping does not exist. There is no way to find out what collection a specific game object belonged to before compilation. Nor is it possible to manipulate all the objects in a collection at once. If you need to do such operations, you can easily do the tracking yourself in code. Each object’s identifier is static, it is guaranteed to stay fixed throughout the object’s lifetime. This means that you can safely store the identity of an object and use it later.

Absolute addressing

It is possible to use the full identifiers described above when addressing. In most cases relative addressing is preferred since it allows for content reuse, but there are cases where absolutely addressing becomes necessary.

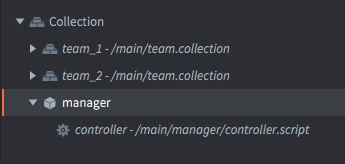

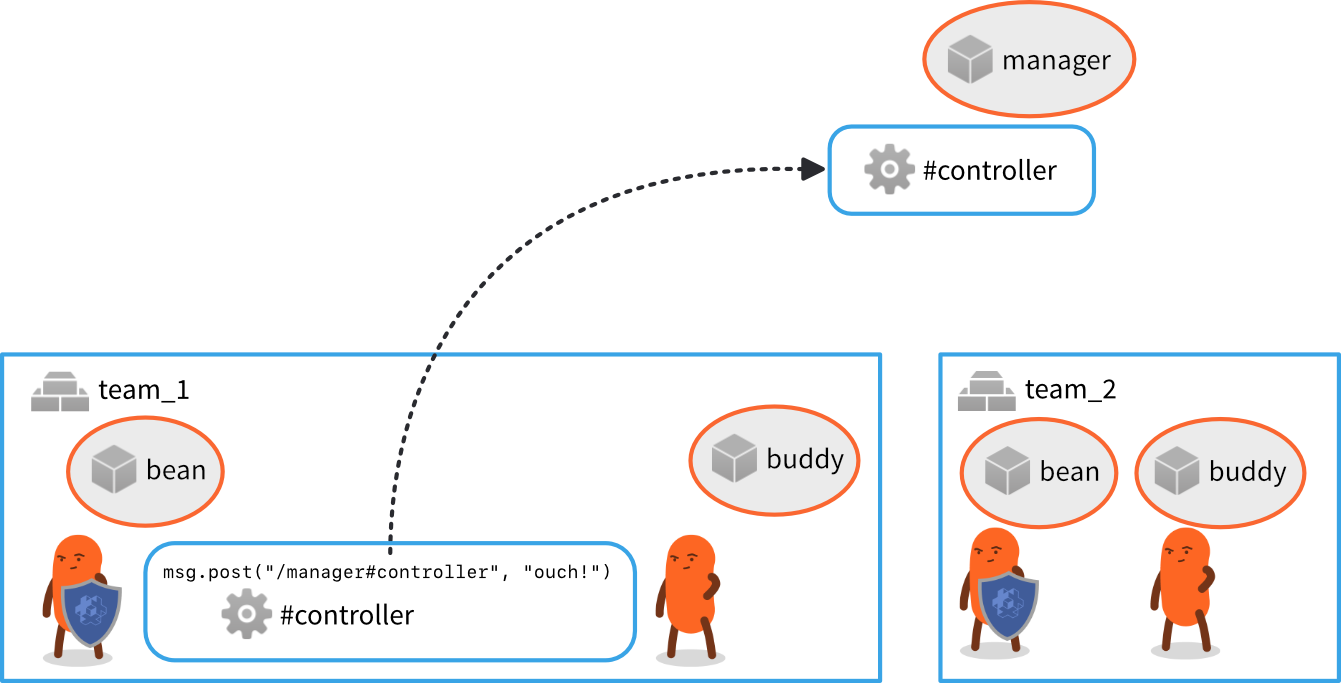

For example, suppose that you want an AI manager that tracks the state of each bean object. You want beans to report their active status to the manager, and the manager makes tactical decisions and gives orders to the beans based on their status. It would make perfect sense in this case to create a single manager game object with a script component and place that alongside the team collections in the bootstrap collection.

Each bean is then responsible for sending status messages to the manager: “contact” if it spots an enemy or “ouch!” if it is hit and takes damage. For this to work, the bean controller script uses absolute addressing to send messages to the component “controller” in “manager”.

Any address that starts with a ‘/’ will be resolved from the root of the game world. This corresponds to the root of the bootstrap collection that is loaded on game start.

The absolute address of the manager script is "/manager#controller" and this absolute address will resolve to the right component no matter where it is used.

Hashed identifiers

The engine stores all identifiers as hashed values. All functions that take as argument a component or a game object accepts a string, hash or an URL object. We have seen how to use strings for addressing above.

When you get the identifier of a game object, the engine will always return an absolute path identifier that is hashed:

local my_id = go.get_id()

print(my_id) --> hash: [/path/to/the/object]

local spawned_id = factory.create("#some_factory")

print(spawned_id) --> hash: [/instance42]

You can use such an identifier in place of a string id, or construct one yourself. Note though that a hashed id corresponds to the path of the object, i.e. an absolute address:

The reason relative addresses must be given as strings is because the engine will compute a new hash id based on the hash state of the current naming context (collection) with the given string added to the hash.

local spawned_id = factory.create("#some_factory")

local pos = vmath.vector3(100, 100, 0)

go.set_position(pos, spawned_id)

local other_id = hash("/path/to/the/object")

go.set_position(pos, other_id)

-- This will not work! Relative addresses must be given as strings.

local relative_id = hash("my_object")

go.set_position(pos, relative_id)

URLs

To complete the picture, let’s look at the full format of Defold addresses: the URL.

An URL is an object, usually written as specially formatted strings. A generic URL consists of three parts:

[socket:][path][#fragment]

- socket

- Identifies the game world of the target. This is important when working with Collection Proxies and is then used to identify the dynamically loaded collection.

- path

- This part of the URL contains the full id of the target game object.

- fragment

- The identity of the target component within the specified game object.

As we have seen above, you can leave out some, or most of this information in the majority of cases. You almost never need to specify the socket, and you often, but not always, have to specify the path. In those cases when you do need to address things in another game world then you need to specify the socket part of the URL. For instance, the full URL string for the “controller” script in the “manager” game object above is:

"main:/manager#controller"

and the buddy controller in team_2 is:

"main:/team_2/buddy#controller"

We can send messages to them:

-- Send "hello" to the manager script and team buddy bean

msg.post("main:/manager#controller", "hello_manager")

msg.post("main:/team_2/buddy#controller", "hello_buddy")

Constructing URL objects

URL objects can also be constructed programmatically in Lua code:

-- Construct URL object from a string:

local my_url = msg.url("main:/manager#controller")

print(my_url) --> url: [main:/manager#controller]

print(my_url.socket) --> 786443 (internal numeric value)

print(my_url.path) --> hash: [/manager]

print(my_url.fragment) --> hash: [controller]

-- Construct URL from parameters:

local my_url = msg.url("main", "/manager", "controller")

print(my_url) --> url: [main:/manager#controller]

-- Build from empty URL object:

local my_url = msg.url()

my_url.socket = "main" -- specify by valid name

my_url.path = hash("/manager") -- specify as string or hash

my_url.fragment = "controller" -- specify as string or hash

-- Post to target specified by URL

msg.post(my_url, "hello_manager!")

- English

- 中文 (Chinese)

- Español (Spanish)

- Français (French)

- Νεοελληνική γλώσσα (Greek)

- Italiano (Italian)

- Język polski (Polish)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Русский (Russian)

- Українська (Ukranian)

Did you spot an error or do you have a suggestion? Please let us know on GitHub!

GITHUB