Defold for Unity users

If you have prior experience with Unity, this guide helps you become productive in Defold quickly. It focuses on essentials and points you to the official Defold manuals whenever deeper details are needed.

Introduction

Defold is a completely free, truly cross-platform 3D game engine with an Editor for Windows, Linux, and macOS. The full source code is available on Github.

Defold is focused on performance, even on low-end devices. Its component-based and data-driven architecture is a bit similar to Unity’s DOTS approach.

Defold is much smaller than Unity. Engine size with empty project is between 1-3 MB on all platforms. You can strip out additional parts of the engine, and move some game content into Live Update to download separately later. A size comparison and other reasons to choose Defold are described on the Why Defold webpage.

To customize Defold to your needs, you can write your own or use existing:

- Fully scriptable rendering pipeline (render script + materials/shaders) with few backends to choose from (OpenGL, Vulkan, etc.).

- Code and components as Native Extensions (C++/C#).

- Editor Scripts and UI widgets to customize Editor.

- Altered build of the engine and editor, as the full source code and a build pipeline is available.

We also recommend checking out a video by Game From Scratch about Defold for Unity developers.

Installation

- Download Defold for your OS.

- Unzip it and launch.

That’s it. No hub, no additional SDK, toolchains or platform bundles installation. That’s why we say Defold has zero setup.

If you need more details read this short Installation manual.

Versions

Defold is updated frequently and does not have an “LTS” track. We recommend using the newest version always. New versions are released regularly - usually monthly, with about two weeks of public beta. You can update Defold directly in the Editor.

Welcome screen

Defold greets you with a welcome screen similar to the Unity Hub, where you can open recent projects:

Or start a new one from:

Templates- basic empty projects for quicker setup for a specific platform or genre,Tutorials- guided learning tours that help you take your first steps,Samples- official or community-contributed use cases and examples,

When you create your first project and/or open it, it will open in the Defold Editor.

Hello World

This is a quick way to get something done in Defold quickly, follow the steps, and then get back to read the rest of the manual.

- Select an empty project from

Templates, name it inTitle, choose location and create it by clickingCreate New Project. It will open in the Defold Editor.

- On the left side, in the

Assetspane, open themainfolder and double click on themain.collectionto open it. - On the right side, in the

Outlinepane right-click on theCollectionand selectAdd Game Object.

- Right-click on the created

gogame object and selectAdd Component, and thenLabel.

- Below, on the left side, in the

Propertiespane type something in theTextproperty. - In the main, central scene view, drag, move and drop the label to position around

(480,320,0), or change it inProperties:Position.

- After changing the label position, save the project by clicking

File->Save Allor shortcut Ctrl+S (Cmd+S on Mac). - Built your project by clicking

Project->Buildor shortcut Ctrl+B (Cmd+B on Mac).

You just build your first project in Defold and should see your text in the window. The concepts of game object and component should be familiar to you. The collections, outline, properties and why we needed to move the label a bit in the top-right direction are explained below.

Defold Editor Overview

We’ll present the Defold Editor here from the perspective of what a Unity user might want to know at first, but we encourage you to check out the full Editor Overview manual after.

Editors comparison

The first difference you’ll notice between Unity and Defold is the default Editor layout. We’re showing a Unity Editor with a slightly modified layout to match Defold’s default layout. They’re placed side by side for easier visual comparison of the main panes, as you should more easily recognise the Unity tabs.

By default, the Defold Editor opens in a 2D orthographic preview. If you’ll be working on a 3D project, or just want an experience closer to Unity — we recommend switching from 2D to 3D by unchecking a 2D toggle in the toolbar and changing the camera projection to perspective by checking Perspective toggle:

You can also adjust the Grid Settings in the toolbar to use the Y plane, as in Unity:

Defold panes overview

The Defold Editor is divided into 6 main panes.

Below is a comparison of Defold naming and functional differences:

| Defold | Unity | Differences |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Assets | Project (Assets Browser) | In Defold Assets pane is docked on the left. Defold does not create any meta files. |

| 2. Main Editor | Scene View | The Defold Editor is context-sensitive (different editors for different file types), while Unity uses separate specialized windows (e.g., Animator, Shader Graph). Defold also has a built-in code editor. |

| 3. Outline | Hierarchy | Defold reflects only the currently opened file or the selected element (game object or component), not a global hierarchy. |

| 4. Properties | Inspector | Defold shows only the properties for the current selection in the Outline, not for all components in the game object. |

| 5. Tools | Console | Defold provides tools in tabs such as Console, Curve Editor, Build Errors, Search Results, Breakpoints, and the Debugger. |

| 6. Changed Files | Unity Version Control (Plastic) | In Defold, once Git is integrated into your project, changed files are shown here. You can still use Git externally. |

Other useful Editor related naming:

| Defold | Unity | Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Game Build | Game Preview | Shows the running game built with the engine. Defold can run multiple instances of the game from the Editor, similar to Unity 6+ Multiplayer Play Mode. In Defold the game always runs in a separate window, not docked. Defold can also run the game on an external device (e.g., a mobile phone), similar to Unity Remote. |

| Tabs | Tabs | Defold allows side-by-side editing in two panes within the Main Editor view. Tabs and panes are docked inside a single Editor window; pane visibility can be toggled (F6, F7, F8) and pane sizes can be adjusted. |

| Toolbar | Toolbar / Scene View Options | Only in newer Unity versions, the transform tools have been moved into the Scene view, similar to Defold. |

| Console | Console | Defold Console is not detachable. Build errors in Defold appear in a separate Build Errors tab. |

| Build Errors | Compilation Errors in Console | Lua scripts are interpreted, so there are no compilation errors. However, your project is built, and some errors may appear during the build. Defold also uses a Lua Language Server for static analysis for scripts. |

| Search Results | Search / Project Search | Filtering by types and labels is not present in Defold. |

| Curve Editor | Unity Curve Editor | Defold Curve Editor allows editing curves for particle effect properties only. |

| Debugger | Visual Studio Debugger | Debugger is fully integrated in Defold out of the box. There is an additional tab to track, enable and disable breakpoints. |

Key Concepts

If you generalize enough, the key concepts behind most game engines are very similar. They’re meant to help developers build games more easily, like assembling blocks, while handling complex and platform related tasks on their own.

Building Blocks

Defold operates with just a few basic building blocks:

For more details, check the full manual about Defold building blocks.

Game Objects

Defold uses “Game Objects”, similar to Unity. In both engines, game objects are containers for data with an ID, and they all have transforms: position, rotation, and scale, but in Defold, the transform is built-in rather than a separate component.

You can create parent-child relationships between game objects. In Defold, this can be done only in the Editor inside a “Collection” (explained below) or dynamically in script. Game objects cannot contain other game objects as nested objects the way they can in Unity.

Components

In both engines, Game Objects can be extended with “Components”. Defold provides a minimal set of essential components. There is less distinction between 2D and 3D than in Unity (e.g., colliders), so there are fewer components overall, and some from Unity you may miss.

Read more about Defold Components here.

The table below presents similar Unity components for quick lookup, with links for each Defold component manual:

| Defold | Unity | Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Sprite | Sprite Renderer | In Defold, you can change the tint (color property) only via code. |

| Tilemap | Tilemap / Grid | Defold has a built-in Tilemap Editor that supports square grids (but there’s an extension for, e.g. Hexagon) and has no built-in autotiling rules. Tools like Tiled, TileSetter or Sprite Fusion have export to Defold options. |

| Label | Text / TextMeshPro | Defold has a RichText extension for rich formatting (similar to TextMeshPro). |

| Sound | AudioSource | Defold has only a global sound source (not spatial). There is an official FMOD extension for Defold. |

| Factory | Prefab Instantiate() | In Defold, a Factory is a component with a specific prototype (prefab). |

| Collection Factory | - (No direct component equivalent) | A Collection Factory component in Defold can spawn multiple Game Objects with parent-child relationships at once. |

| Collision Object | Rigidbody + Collider | In Defold, physics objects and collision shapes are combined in a single component. |

| Collision Shapes | BoxCollider / SphereCollider / CapsuleCollider | In Defold, shapes (box, sphere, capsule) are configured inside the Collision Object component. Both support collision shapes from tilemaps and convex hull data. |

| Camera | Camera | In Unity, the camera has some more built-in rendering and post-processing settings, while Defold delegates it for custom control for user via the render script. |

| GUI | UI Toolkit / Unity UI / uGUI Canvas | Defold GUI is a powerful component for building complete UIs and templates. Unity doesn’t have an equivalent single UI component, rather multiple UI frameworks. Defold has an extension for Extension too. |

| GUI Script | Unity UI / uGUI scripts | Defold GUI can be controlled via GUI scripts using the dedicated gui API. |

| Model | MeshRenderer + Material | In Defold, a Model component bundles a 3D model file, textures, and a material with shaders. |

| Mesh | MeshRenderer / MeshFilter / Procedural Mesh | In Defold, Mesh is a component for managing a vertex set via code. It’s similar to a Defold Model, but even more low-level. |

| ParticleFX | Particle System | Defold’s particle editor supports 2D/3D particle effects with many properties, and lets you animate them over time using curves in the Curve Editor. It has no Trails or Collisions. |

| Script | Script | More details on programming differences explained below. |

Extensions and custom components

Defold also has an official Spine and Rive components available via extensions.

You can also create your own custom Components using Native Extensions, like e.g. this community created Object Interpolation Component.

Some Unity components have no out-of-the-box equivalent in Defold, for example: Audio Listener, Light, Terrain, LineRenderer, TrailRenderer, Cloth or Animator. However, all of this functionality can be implemented in scripts, and there are already solutions available—for example, different lighting pipelines, the Mesh component for generating arbitrary meshes (including terrain), or Hyper Trails for customizable trail effects. Defold may also add new built-in components in the future, such as lights.

Resources

Some Components require “Resources”, similar to Unity, for example, sprites and models need textures. A few of them are compared in the table below:

| Defold | Unity | Differences |

|---|---|---|

| Atlas | Sprite Atlas / Texture2D | Defold also has an extension for Texture Packer. |

| Tile source | Tile Palette + Asset | In Defold, a tile source can be used as the texture for tilemaps, but also for sprites or particles. |

| Font | Font | Used by the Defold Label component or text nodes in GUI, similar to Text/TextMeshPro in Unity. |

| Material | Material | In Defold, shaders are named: vertex program and fragment program. |

Collection vs Scene

In Defold Game Objects and Components can be placed in separate files, like Unity prefabs, or be defined in a combining “Collection” file.

A Collection in Defold is essentially a text file with a static scene description. It is not a runtime object. It only defines what Game Objects should be instantiated in the game and how parent-child relationships between those objects should be established.

Game Worlds

Unity scenes share by default the same global game state and physics simulation, effectively the same world. In Defold, you have two options:

- Instantiate game objects from a single game object file via a

Factoryor a collection file via aCollection Factoryto a given, instantiated already world, like prefabs. - Create a separate game world at runtime, with its own game objects, physics world, engine operations and addressing namespace via a collection loaded at bootstrap or via a

Collection Proxycomponent.

Factories and Proxy components are also explained below. Read more about Collections in the Building Blocks manual.

Project Resources and Assets

Unity and Defold both store game content in the project directory, but they differ in how assets are tracked and prepared.

Assets

Unity keeps assets in Assets/ and generates .meta files. Defold has no meta files. The project in Defold is just your folder structure, precisely like on disk - and the Assets pane mirrors it always.

Resource Formats

Unity imports and converts assets into some other formats behind the scenes. In Defold, you work directly with source resources (.png, .gltf, .wav, .ogg, etc.) and assign them to Components.

Unity can use a single image as a Sprite. In Defold, images can be used directly for Models/Meshes, but Sprites/GUI/Tilemaps/Particles require an atlas (packed textures) or a tilesource (grid-based tiles).

Most Defold resources are stored as text, which is version-control friendly.

Library Cache

Unity generates a Library/ folder for imported assets. Defold doesn’t have such a directory; assets are processed during builds, with cached outputs under the build folder (and optional local/remote build caches).

Code Writing

A common pitfall for developers coming from Unity is treating Defold scripts like MonoBehaviour and attaching one to every game object. While you can definitely write in an object oriented way, there are even libraries to help you with this, the recommended way, especially with many of the same game objects is to use scripts as systems or managers. A single script can control hundreds or thousands of objects and their components, while having no scripts of their own, thanks to powerful addressing and messaging in Defold. Creating a separate script for each object is rarely necessary and can lead to a counterproductive complexity.

An example showing how to utilise Defold script properties, factories, addressing, and messaging to control multiple units can be found here.

Good manuals on code writing:

Lua

Defold scripts are written in a dynamically typed, multi-paradigm Lua language.

There are few types of Lua scripts: *.script, *.gui_script, *.render_script, *.editor_script, and *.lua modules.

Teal

Defold supports the usage of transpilers that emit Lua code, such as Teal - a statically-typed dialect of Lua, but this functionality is more limited and requires additional setup. Details are available in the Teal Extension Repository.

C++/C# Native Extensions

In Defold you can write Native Extensions in C++ and C#. If you are very comfortable with C#, it’s technically possible to structure most of your game logic in a C# extension and just call it from a small Lua bootstrap script, though this requires some advanced API knowledge and is not recommended for beginners.

Read more about extensions in Defold Native Extensions manual.

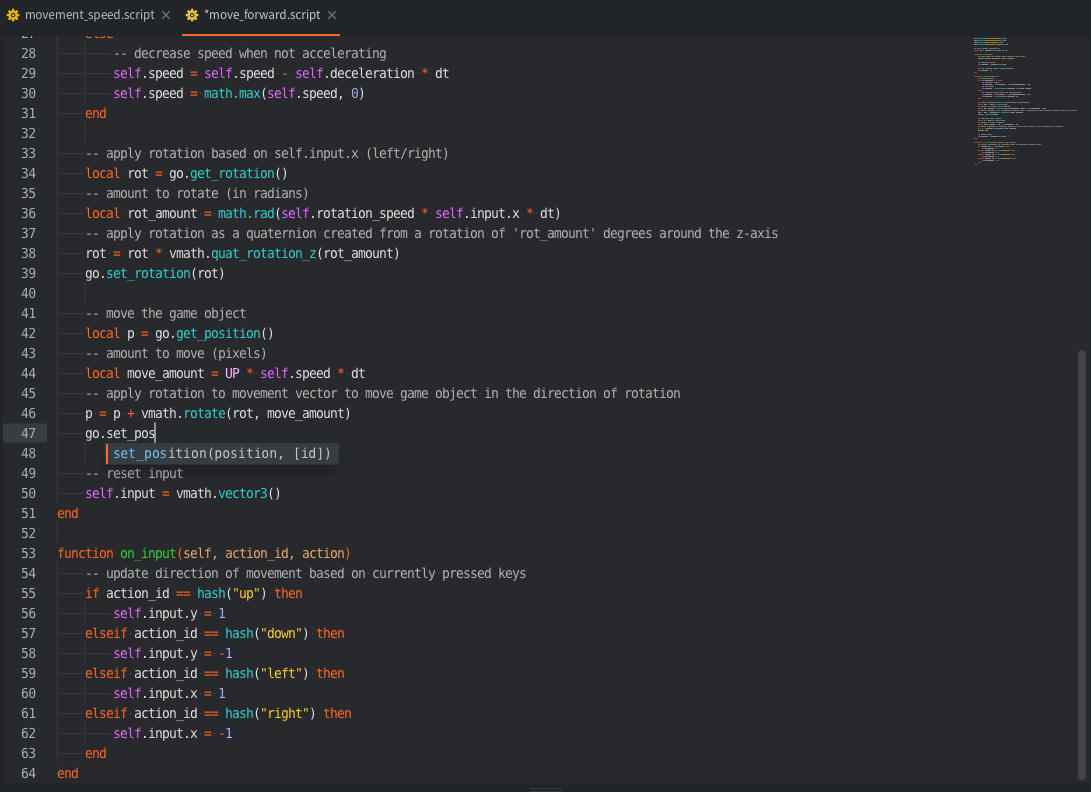

Built-in Code Editor

Defold Editor includes a built-in code editor with code completion, syntax highlighting, quick documentation lookup, linting, and a built-in debugger.

VS Code and other editors

You can still use your own external editor if you prefer. All Defold components and related files are text based, so you can edit them with any text editor, but you must follow the proper formatting and element structure, since they are Protobuf-based.

If you are used to VS Code and want to use it to write your game’s code, we recommend installing Defold Kit or Defold Buddy from the Visual Studio Marketplace.

You can also configure Defold Editor preferences to open text files by default in VS Code (or any other external editor). See Editor Preferences for details.

Shaders - GLSL

Defold uses GLSL (the OpenGL Shading Language) for shaders - Vertex Programs and Fragment Programs, similar to Unity. Although Defold doesn’t offer a Shader Graph like Unity (which may be a downside), you can still create equivalent shaders by writing code.

Read more about shaders in the Shaders manual.

Materials

Defold uses a concept of Material that connects .fp and .vp shaders, samplers (textures) and other things like Vertex Attributes or Constants.

Read more about materials in the Materials manual.

Messaging System

In Defold, objects don’t hold direct references to each other. There’s no GetComponent, no cross-object method calls between scripts, and no global scene access like in Unity.

Instead, scripts communicate via message passing: you send messages to other scripts, rather than calling methods or accessing components directly. What those objects do with the messages is up to them.

This can feel unfamiliar at first, but it promotes loose coupling and reduces tight interdependencies.

Sending a message

In Unity, communication usually looks like this:

var enemy = GameObject.Find("Enemy");

enemy.GetComponent<EnemyAI>().TakeDamage(10);

So objects can directly reference each other and call methods on other scripts. Everything exists in one shared scene space.

In Defold you send a message from one script to another script (or other component):

msg.post("#my_component", "my_message", { my_name = "Defold" })

And can handle those messages in script:

function on_message(self, message_id, messsage)

if message_id == hash("my_message") then

print("Hello ", message.my_name)

end

end

Ignore # and hash for now, we’ll get to this later. The rest should be straightforward. You can send a message to any component (even to the same script) of any instantiated game object.

Components other than scripts

Sometimes you send messages to e.g. Sprite or Collision components, for example, to enable or disable them. Sometimes Components send messages to your script, for example, when collision occurs, so you can handle it. Defold internally uses the same messaging system, for engine events and gameplay communication.

Messaging system is somewhat similar to Unity’s SendMessage or event systems, though the addressing and conventions differ.

You can read more details in the Message Passing Manual.

Addressing

Objects and components in Defold are identified by addresses, known as URLs.

Every instantiated object and component has its own unique address, and you don’t need to traverse a scene graph to find them. This makes addressing explicit and direct.

A simple URL in Defold might look like this:

"/player"

This is conceptually similar to:

GameObject.Find("player")

Now it’s time to explain why "/" or "#" were used in addresses.

Defold URL (similar to URL), consist of three parts:

socket: /path #fragment

or, described more in Defold naming:

collection: /gameobject #component

Spaces are added in the above descriptions only to separate those 3 parts visually.

So simply put:

collection:identifies the collection context, with:at the end./pathidentifies the Game Object, with/preceding the ID.#fragmentidentifies the specific component on that object (such as a script, sprite, or collision component), with#preceding the ID.

Static address

Those identifiers are determined on creation of each, and never change, even if you alter the parent-child relationships. You can set them in Property Id in files, or you get them in runtime from calls to factory.create or collectionfactory.create, when instantiating.

Relative addressing

You don’t always need to use a full URL.

If you send messages within the same collection (the same world), you can omit the socket part:

/gameobject #component

If you are sending to a component within the same game object, you can omit the game object part as well:

#component

Two useful shorthands are:

#for sending to this Script component.for sending to all components in this Game Object

Relative addressing and shorthands allow you to write URLs that are reusable in different contexts and game objects without specifying full paths.

Messaging to GUI and render

Because Defold separates the GUI world from the Game Object world, you can also send messages from your game object .scripts to .gui_scripts.

You can also send messages to special system namespaces using an identifier that starts with @. For example, the render system can be addressed via @render: and you can use this to control certain built-in rendering features, such as changing the projection in the default render script:

msg.post("@render:", "use_stretch_projection", { near = -1, far = 1 })

More details you can find in the Addressing manual.

Prefabs and instances

Unity can instantiate anything in the Scene statically or dynamically, and Defold can do the same. In Unity you take a Prefab and call Instantiate(prefab). In Defold you have 3 components for instantiating content:

Factory- instantiates a single Game Object from a given prototype: a*.gofile (prefab).Collection Factory- instantiates a set of Game Objects with parent-child relationships from a given prototype: a*.collectionfile.Collection Proxy- loads and instantiates a new world from a*.collectionfile.

Factory

Once you have a Factory component defined with its Prototype property set to the appropriate Game Object file, spawning is as simple as calling in code:

factory.create("#my_factory")

This uses the address of the component, in this case - a relative path using the identifier "#my_factory".

It returns the identifier of the newly created instance, so if you need to use it later, it’s worth storing it in a variable:

local new_instance_id = factory.create("#my_factory")

Remember that in Defold you don’t need to manually pool objects - the engine itself does pooling internally for you.

Check more details in the Factory manual.

Collection Factory

The difference between Factory and Collection Factory component is that Collection Factory can spawn multiple game objects at once, and define at creation the parent-child relationships as defined in the *.collection file.

Such a distinction is not present in Unity, it doesn’t have a dedicated concept that matches Defold’s Collection Factory. The closest analogy is just a nested Prefab that contains a hierarchy of objects.

It returns a table with ids of all spawned instances:

local spawned_instances = collectionfactory.create("#my_collectionfactory")

Check more details in the Collection Factory manual.

Custom properties of instances

When calling factory.create() or collectionfactory.create() you can also specify optional parameters such as position, rotation, scale and script properties, so you can control exactly how and where the instance appears, and how it behaves e.g.:

factory.create("#my_factory", my_position, my_rotation, my_scale, my_properties)

Dynamic Loading

In both Factory and Collection Factory components you can mark a Prototype for dynamic resource loading so that its heavy assets are only pulled into memory when needed, and unloaded when they’re no longer used.

Check more details in the Resource Management manual.

Collection Proxy

The Collection Proxy refers to a specific *.collection file, but instead of injecting the objects into the current world (like factories), it loads and instantiates a new game world. This is somewhat similar to loading an entire scene in Unity, but with stricter separation.

In Unity you might load an additive scene like this:

SceneManager.LoadSceneAsync("Level2", LoadSceneMode.Additive);

In Defold you load the new collection just by sending a message to the Collection Proxy component:

msg.post("#myproxy", "load")

- When you send the proxy a message

"load"(or"async_load"for asynchronous loading), the engine allocates a new world, instantiates everything in that collection there, and keeps it isolated. - Once loaded, the proxy sends back a

"proxy_loaded"message indicating the world is ready. - You then typically send

"init"and"enable"messages so the objects in that new world begin their normal lifecycle.

To communicate between the loaded worlds, you have to use explicit messaging with URLs that include the world name (collection:, the first part of the URL).

This isolation can be a huge advantage when implementing level transitions, mini-games, or large modular systems, because it prevents unintended interactions, and also allows separate control over update timing if needed (e.g. for pause or slow motion).

If you’ve ever used multiple scenes in Unity and needed them to behave independently, think of a Collection Proxy as a way to bring that concept directly into Defold.

Check more details in the Collection Proxy manual.

Application Lifecycle

You’re familiar with a set of Unity lifecycle events: Awake, Start, Update, FixedUpdate, LateUpdate, OnDestroy or OnApplicationQuit.

Defold also has a well-defined application lifecycle, but the concepts and terminology differ. Defold exposes lifecycle stages through a set of predefined Lua callbacks that are called by the engine during initialization, each frame, and finalization.

Here’s a comparison:

| Defold | Unity | Comment |

|---|---|---|

init() |

Awake() / Start() / OnEnable() |

Defold has a single initialization entry point and callback - init(). It is called on every component on its creation. |

on_input |

Input Methods | Defold receives inputs, when input focus is set for the script. Processed first in the update loop. |

fixed_update() |

FixedUpdate() |

Called at fixed timestep. To enable it in Defold, you have to set the Use Fixed Timestep - details. Since 1.12.0 it runs before update(). |

update() |

Update() |

Called once per frame with delta time. |

late_update() |

LateUpdate() |

Called after update(), just before the frame renders. Available since 1.12.0. |

on_message |

Message Receiver | Defold’s core callback for receiving messages. Processed when any message is in a queue. |

final |

OnDisable / OnDestroy / OnApplicationQuit |

Defold calls final() callbacks for each component when its game object is destroyed in runtime (using go.delete()) or world/collection is unloaded and during application termination for all remaining objects. |

::: sidenote Remember that Defold doesn’t guarantee any order of execution between components, when multiple ones are initialized/updated/removed at once. Decoupled design is encouraged.

Initialization

Think of Defold’s init() as combining elements of Unity’s Awake(), Start() and OnEnable() into a single entry point where the engine has already set everything up and you can safely prepare your component state.

When messages are handled?

Because you can already post messages in init(), the messages are dispatched first just after the initialization.

Messages are handled then after each internal processing loop, every time there is something in a queue, so on_message() can be called, for example, even several times in an update loop.

Update loop

Every frame, Defold runs through a sequence of operations — handling input, dispatching messages, triggering script and GUI updates, applying physics, transforms, and in the end rendering graphics.

Finalization

In Defold, cleanup is always tied to deletion or unloading of the world, and your only per-component exit hook is final().

A subtle difference from Unity’s model is that there is no distinction between a component being disabled and the entire application quitting.

Rendering

Render script (*.render_script) is a part of the rendering pipeline, which also participates in the lifecycle with its own init(), update(), and on_message() callbacks, but they operate on the render thread and are separate from game object and GUI script logic.

For further details read the Application Lifecycle Manual.

GUI

Defold’s GUI is a whole single dedicated framework for User Interfaces - menus, overlays, dialogs, and other elements, similar to UI Toolkit or uGUI with Canvas.

GUI is a Component, and is separate from Game Objects and Collections. Instead of Game Objects, you work with GUI nodes arranged in a hierarchy, driven by a GUI script.

GUI Nodes

When you open a *.gui component file in Defold, you are presented with canvas where you place "GUI nodes". These are the building blocks of the GUI. You can add GUI nodes of type:

- Box (rectangular shape with a texture)

- Text (with any font)

- Pie (radial fill pie-slice element with a texture)

- ParticleFX

- Template (another whole nested

.guifile, like a GUI prefab) - and Spine node, when using Spine extension.

GUI Script

GUI component have a special property for GUI scripts - you assign one *.gui_script file per component and it allows to modify the behaviour of the component, so it’s very similar to regular scripts, except it doesn’t use the go.* namespace (which is for game object scripts). Instead, it uses a special gui.* namespace API that only works inside GUI scripts (*.gui_script). You can think of it like a separate Scene. Unity UI (uGUI) with Canvas.

GUI Rendering

GUI elements are rendered independently of the game camera, typically in screen-space, but this behavior can be changed in custom rendering pipelines.

For further details read the GUI Manual.

Where are Sorting Layers?

This is a very common Unity migration confusion.

GUI components have Layers and this works almost the same as “Sorting Layers” in Unity, but for other components, like Sprites, Tilemaps, Models, etc, there is no direct equivalent.

Instead, you typically combine:

- Fine ordering via Z axis when using a default camera or depth when using a Camera component.

- Coarse ordering via the render script using render predicates - to select what to draw by material tags.

But you shouldn’t mimic Unity Sorting Layers with lots of tags, because in Defold, tags are a render-level mechanism. Overusing them can break batching and raise draw overhead.

Where to go from here?

If you have questions or get stuck, the Defold Forum or Discord are great places to reach out for help.

- Defold for Unity users

- Introduction

- Installation

- Versions

- Welcome screen

- Hello World

- Defold Editor Overview

- Editors comparison

- Defold panes overview

- Key Concepts

- Building Blocks

- Game Objects

- Components

- Resources

- Collection vs Scene

- Project Resources and Assets

- Assets

- Resource Formats

- Library Cache

- Code Writing

- Lua

- Teal

- C++/C Native Extensions

- Built-in Code Editor

- VS Code and other editors

- Shaders - GLSL

- Messaging System

- Sending a message

- Addressing

- Messaging to GUI and render

- Prefabs and instances

- Factory

- Collection Factory

- Collection Proxy

- Application Lifecycle

- Initialization

- When messages are handled?

- Update loop

- Finalization

- Rendering

- GUI

- GUI Nodes

- GUI Script

- GUI Rendering

- Where are Sorting Layers?

- Where to go from here?

- English

- 中文 (Chinese)

- Español (Spanish)

- Français (French)

- Νεοελληνική γλώσσα (Greek)

- Italiano (Italian)

- Język polski (Polish)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Русский (Russian)

- Українська (Ukranian)

Did you spot an error or do you have a suggestion? Please let us know on GitHub!

GITHUB